- Home

- Katharine Graham

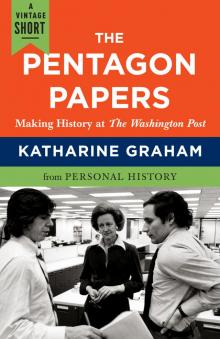

The Pentagon Papers

The Pentagon Papers Read online

Katharine Graham

Katharine Graham is fondly remembered as the powerful longtime publisher of The Washington Post. She died in 2001.

The Pentagon Papers

Making History at the Washington Post

from Personal History

Katharine Graham

A Vintage Short

Vintage Books

A Division of Penguin Random House LLC

New York

Copyright © 1997 by Katharine Graham

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published as part of Personal History in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, in 1997.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data for Personal History is available from the Library of Congress.

Vintage eShort ISBN 9780525563662

Cover photograph © Mark Godfrey/The Image Works

www.vintagebooks.com

v5.1

a

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

The Pentagon Papers

COINCIDING WITH CHANGES in the company came further changes in the country, not the least of which was Richard Nixon’s inauguration in 1969 and the beginning of his administration. Nixon had a long-standing problem with the press as a whole and the Post in particular. Twice, he had angrily canceled his subscription to the paper. But at least at the beginning of his administration things were civil, if not friendly, between us. Basically, I was reserving judgment. After he had been in office only two weeks, I wrote Ken Galbraith, “The Nixon group is still a puzzle, as no one knows what he—or they—are for. Apparently nothing they were discussing pre-election, but that’s par, isn’t it?”

In March, President Nixon called me to suggest that I invite Henry Kissinger to an editorial lunch to brief us on administration thinking on Vietnam. The very next week, Kissinger came to lunch, a meeting that was the start of a long relationship with the paper and with me. All of the top editors and reporters from the Post were there, as well as a few from Newsweek’s Washington bureau. We all noted with interest that Nixon sent Kissinger, not Bill Rogers, his secretary of state. (Bill’s had been a significant departure for me and for the company, since he had been a friend as well as our legal adviser.)

“We inherited a mess,” Henry said, in answering a question about whether the new administration didn’t appear to be almost as hawkish as Johnson’s. He emphasized that LBJ had sent half a million men to Vietnam with no overall policy. Though Vietnam was the primary focus of the lunch, we also talked about arms control and nuclear proliferation. It was clear that Henry was brilliant, and at lunch that day he was both funny and articulate.

My relationship with Nixon was very different. I went to the Nixon White House twice in 1969, once for the farewell dinner for Chief Justice Earl Warren, who had resigned from the Supreme Court, and the second time for a dinner for the Associated Press directors, at which local publishers were included. Incredibly, I received a letter from Nixon in June of his first year in office congratulating me on being one of four women given awards as “Distinguished Women in Journalism.” Nixon’s letter, no doubt staff-written, read: “This is a just tribute to your outstanding career and example. There are few women in our nation held in such high opinion by their peers. We are glad to count ourselves among your admirers.”

This admiring attitude didn’t last long. Whatever Lyndon Johnson’s feelings had been about the press in general or me in particular, I began to realize how much I missed him. The atmosphere between the Nixon administration and the media quickly became embattled. That very fall, the war on the “Eastern establishment elitist press” began in earnest, and the Post was dragged into the middle of it. In mid-November, Nixon made a tough speech on Vietnam, implying that most of the American people supported him in what he was doing and that only the press was critical.

A reaction to Nixon came in the form of the biggest antiwar rally ever held in Washington. When asked for his response to it, Nixon said he had been watching football, a reaction that the Post compared to Marie-Antoinette’s “Let them eat cake.” The following week, Vice-President Agnew selected the Post for particular attention, saying in a speech that we were “an example of a trend toward monopolization.” He was not recommending the dismemberment of The Washington Post Company, he emphasized, but “merely pointing out that the public should be aware that these four powerful voices”—he counted our all-news radio station, along with the Post, Newsweek, and our television stations—“harken to the same master.” When I first heard his allegation that all the branches of the company answered to one voice—mine—I was flabbergasted at such a lack of understanding.

My defending The Washington Post Company in these years, and what we were doing or saying or publishing, was instinctive. Since I believed so much in our mission, it wasn’t hard to do. My response to this diatribe of Agnew’s was to insist that the various divisions of our company decidedly did not “grind out the same editorial line.” On the contrary, each branch operated autonomously, and they all competed vigorously with one another, even disagreeing on many issues. In addition, I pointed out that by any objective standard the Post and WTOP were operating in one of the most competitive communications cities in America.

Agnew’s words had landed on fertile ground in an emotional environment. It wasn’t just Vietnam and civil rights that were tearing the country apart and preoccupying us; there was a social revolution going on. There is no doubt that he worried all of us—perhaps more than he should have—by striking a popular chord in a vulnerable area. Once he got a positive response, he kept up his harangues, pouring on the heat—egged on, we increasingly felt, by Nixon himself.

Toward the end of November, Phil Geyelin [Post editorial page editor] was at a dinner with Herb Klein, press officer at the White House, and sent me a memo afterwards about their conversation, during which Phil had asked Klein if what we were facing was a concerted campaign from the White House and to what extent the president exercised control over it. Klein’s reply: “The president tells them which way to go…but he can’t read speeches in advance.” If there was another speech by Agnew, Phil asked Klein, could it be “laid at Nixon’s doorstep?” He also asked if Klein conceded that we might have reason to wonder what such an attitude on the part of the administration meant for the renewal of our television and radio licenses. Klein felt that Agnew’s speeches guaranteed we’d get our licenses, since so many people would be watching. This was all, of course, before Watergate, and a real foreshadowing of things to come.

Soon after this exchange, on December 17, Newsweek’s Washington-bureau chief, Mel Elfin, invited Agnew to dinner at his house, along with certain reporters from the bureau, editors from New York, and me. The main discussion of the night centered on why Agnew had taken after the press—and, alternately, why the press was so much after Agnew. Mel and Bob Shogan wrote up a long memo of what took place that night. “What we all had for dinner,” they wrote, “was pure essence of Agnew. It was a typical, predictable performance. It may or may not be reassuring to know that the man doesn’t sound or act differently in a semi-private, semi-social situation than he does in public….What made it seem so abrasive—and a little unreal at times—was that we had an unusually intensive dose.”

One of the first things Agnew said that night was, “The real trouble with this administration is that it has bad PR.”

When asked if he cleared his own speeches with the president, he responded, “Except for foreign-policy matters of substance, I don’t clear anything with anybody.” Reporters responded, nearly in chorus, to the effect that, “if he expected us to believe that, why couldn’t he believe that Newsweek, The Washington Post, and our stations didn’t clear everything with Kay Graham?” It was the only point all evening, Mel noted, on which the vice-president “seemed to give a little ground, albeit somewhat grudgingly admitting that maybe he hadn’t fully understood how the Washington Post Co. ran.” But, as Mel wrote, all that had been said throughout the evening seemed only to have been

…preparation for the veep’s big curtain speech. Agnew must have been rehearsing it in his mind as the rest of us chattered away while he glanced continually at his watch. Suddenly there was silence and Spiro spoke. Out of the past Caligula’s horse came galloping again, providing a cognomen and a symbol for the evening, something like Citizen Kane’s “Rosebud.” “I want you to know how I feel about things,” the veep said, in his most candid manner. “To refer to me as Caligula’s horse is intellectual dishonesty.” Then beaming like a man who has struck precisely the right blow he pranced out of the room and into the night….

Despite these unsettling strains, there was still a good deal of traffic between the administration and people throughout the Post Company. I was trying to keep open the channels of communication, and for the most part during the first year of the Nixon administration everything remained polite and professional. We had several administration people in to editorial lunches, including Attorney General John Mitchell. Just after he had come, the Post got into a flap with him because Ken Clawson, a reporter who later joined the administration, misquoted him in a story. We ran a correction in the same place where the mistake had been made, on the front page, and the attorney general wrote me a pleased letter, saying, “Now you can see why I say The Post is the best paper in the country.” I should have framed the letter.

I also had professional dealings and even some social relations with John Ehrlichman. As head of a committee trying to deal with crime in the District, I had first met Ehrlichman when I went to him to seek aid for funding more police, at which time I found him helpful and even fun. At one point early in 1971, in a regular daily column that appeared in the Post called “Activities in Congress,” we had, through a typographical error, mistakenly identified Ehrlichman as a “White Mouse aide.” He had clipped the piece and sent it to me with a note saying, “For a while now I have suspected that The Post thought the President was a rat. Now it appears that you have turned your calumny on the rest of us—oh opprobrium! Perhaps there will be a place at Disneyland for me when all of this is a memory.” I responded in kind, saying I understood we had not only termed him a mouse aide, “but a white mouse aide, thus introducing a note of racial prejudice,” and asking if he intended to “launch a full-scale fairness investigation.”

As time went on, I saw much more of Henry Kissinger. He was still single and occasionally asked me out to do something casual at night. Much later, when he married Nancy Maginnes, I worried that he would go out of my life; I didn’t know Nancy, and wasn’t sure how we’d get along. Gradually, however, we three formed a close friendship that flourishes to this day. People have often asked how I handled friends like Henry insofar as the paper was concerned. It varied with different people, but certainly no one at the Post or Newsweek went any easier on Henry because we were friends—in fact, our friendship may have made things a little harder for him.

Nixon remained puzzling to me. Early in 1970, I had written to Lyndon Johnson saying, “I often think of you. I must say Washington is a very different place. This is the strangest group I can ever remember!” I hadn’t communicated much with LBJ since he and Lady Bird had left Washington in January 1969, but whatever had come between us over the years seemed to fall away, and he wrote me back how glad he was to hear from me. When he sent a large bouquet of flowers around Easter, I felt that the time of frost was over. I called him immediately and asked whether he might be coming to Washington soon and, if so, whether I could do something for him—dinner at my house or an editorial lunch at the Post. Soon the answer came back that he’d like to do both, and the dates were set.

In April, the Johnsons came to R Street for a dinner, the guests at which included some of his oldest friends and my family. Johnson dominated the evening, holding court in the living room before dinner, talking with Lally [Graham’s daughter] and Don at length about their father, reading to them from letters and memos Phil [Philip Graham, Graham’s late husband and former Post publisher] had written him which he’d brought along, and telling them how much Phil had meant to him. It was Johnson at his best and most thoughtful.

But, nice as the evening was, it didn’t hold a candle to lunch the next day, when the top editors and reporters of the Post and Newsweek gathered at the paper. The conversation went on for more than four hours. Two Post reporters, Dick Harwood and Haynes Johnson, later wrote about it movingly and in great detail in their book, Lyndon. They noted how Johnson had had one of a series of heart attacks only a month before this Washington visit. His hair had turned almost completely white and had grown long because, he explained, the ranch was so far from a barbershop that he cut it himself. Though he didn’t look very well, any sign of illness seemed to fade as he began to talk about the problems of the presidency. “Gradually his manner and mood changed,” Harwood and Johnson wrote. “He began talking about Vietnam, and suddenly he was more vigorous and assertive.”

Because he was writing his memoirs, foremost in his mind was his own place in history. He was very concerned with how he and his administration would be viewed and had actually planned for this luncheon meeting, having Tom Johnson—now president of CNN, then still Lyndon’s administrative assistant—bring along some of the most sensitive files so that he could review with us how he had made certain decisions. Tom had brought two briefcases full of top-secret documents about the war in Vietnam, and he later recalled, “There was no other occasion like that that I experienced either inside the White House during his White House years or in his retirement years.”

As he talked, Lyndon would reach behind him to Tom, who knew just what paper he wanted and put it into LBJ’s extended hand—Lyndon was just like the relay runner who reaches behind him for the baton without looking back and while still running. Meg [Meg Greenfield, Post editorial writer], who was seated somewhere between LBJ and Tom, had to keep bobbing back and forth to accommodate Lyndon’s outstretched hand.

As Tom saw it, LBJ used the lunch as a venue for venting some of his feelings and frustrations about things that had worked against his achieving all he had tried to accomplish while in the White House. He started with a detailed chronology of why he had called for the bombing halt in 1967, and how he came to the decision not to run again in 1968. He spelled out the background of each decision in detail, almost minute by minute, complete with typical Johnson language. He talked about his own love-hate relationship with the press and said he agreed with many of Agnew’s criticisms of the press’s liberalisms. He reminisced about his childhood and his entire political career. As he got going, particularly on his own background, he became, as Haynes and Harwood said, “more colloquial and more Texan.” “He was overpowering,” they recalled—a feeling I had, too. He gave us the full Johnson treatment: “He thumped on the table, moved back and forth vigorously, grimaced, licked his lips, gestured with his arms, slumped back into his seat, switched from a sharp to a soft story, and kept the conversation going from the moment he sat down at the table until hours later when Lady Bird called the Post and sent in a note reminding him he should come home and rest.”

By that time, late in the afternoon, LBJ had become more serious and philosophical. He recounted with pride his domestic achievements and spoke of the three men who had been most influential in his life: his daddy; Franklin Roosevelt, “who was like a daddy to me”; and Phil Graham—omitting Sam Raybu

rn, who certainly should have been on that list. “Phil used to abuse me and rail at me and tell me what was wrong with me,” Lyndon recalled, “and just when I was ready to hit him, he’d laugh in that way of his to let me know he loved me. And he made me a better man.”

When, at last, he did get up to leave and we were all standing, he told a final story, filled with friendly feeling. The story was about Sam Rayburn, at the beginning of his political career and still an unknown young man, looking for a place to stay in a small Texas town. Everyone turned him down—all the important people, including the bankers, the newspaper editor, the judge. Only an old blacksmith agreed to take him in for the night. Much later, now famous and powerful, Rayburn returned to the town, this time with everyone wanting him. He told them all no and asked for the old blacksmith. The two of them stayed up very late talking, and when Rayburn finally said he had to get to sleep, the blacksmith said, “Mr. Sam, I’d just like to talk to you all night.” That, LBJ concluded, was “the way he felt about his friends at the Post.” Everyone in the room—not all of them Johnson fans by any means—burst spontaneously into applause, something I had never seen before and have not witnessed since. It was a highly emotional farewell.

—

WHILE MY PUBLIC life grew busier and busier, my private life grew even more so. Nevertheless, there were many small and large pleasures in these years, quiet times that I remember still. To some extent, family problems increased. As my mother aged throughout the mid-1960s, she went rapidly downhill physically. Too many years of too much food and drink, combined with too little exercise, had made her overweight as well as arthritic. When a psychiatrist finally succeeded in getting her to reduce her drinking, it was too late for her to retrieve her mobility but not too late to recover her control of her interests and pursuits. She was back again, exercising her authority, criticizing, and arguing. It was quite a comeback, and she was in very good form for the last few years of her life, which she lived to the fullest, with all her mental faculties intact right to the end.

The Pentagon Papers

The Pentagon Papers